#Receptiogate and gate-keeping

As I said in my previous post, the first topic I want to consider in reflecting on the so-called Receptio affair is what it tells us about the limits of the scholarly community. We can begin by noting what has been perhaps the most eye-catching feature of the controversy: the unravelling of the identity of the Research Centre for European Philological Tradition, of which Prof. Carla Rossi is Director. The Centre, which takes Receptio as an acronym for its full title, has an elegant website. On that was listed an impressive number of employees and associates. What became clear was that the photos used for some of those people were stock head-and-shoulders images that already had multiple outings elsewhere on the internet. It also became apparent that some of those mentioned were members of Prof. Rossi’s family. For others, it has proven difficult to verify their existence, including that of Prof. Rossi’s secretary. Meanwhile, other online searches focussed on the two addresses given on the site, with that for ‘in person’ visits being in London, and the ‘operative headquarters’ being in Lugano; in the UK case, there were doubts about how far this was an active office, and in the case of the Lugano address, about whether it was a private address.

None of these findings constitute evidence of an act of corruption. The stock photos could be explained by the Centre’s statement that its website is out of date; that is, for sure, an understandable problem, though it does raise the question of why some individuals agreed to be represented, even temporarily, by others’ faces. Engaging family members in an enterprise —however often it is taken in northern Europe as evidence of unacceptable nepotism — is not universally considered malpractice: after all, in the States, spousal appointments happen at universities without, it seems, any moral outrage. What it does suggest is that some involved were not appointed through open competition, as one would expect with a research centre. Likewise, there is nothing shady about working from one’s home, but it undermines the presentation of the Centre as an autonomous institution, with a life which is not dependent on its director.

Cumulatively, these details give the impression that Receptio is — in the sense that Peter Burke uses the term when discussing Louis XIV — a fabrication, or — to shift to Genette’s terminology — a hypertext. I use these terms not as a criticism but as tools of neutral analysis. Carla Rossi has made it clear that her designation as professor is merely titular, and she is in no way ‘un potente barone universitario’. In attempting to carve out a place for her scholarship, she has taken the concept of the research centre and moulded one of her own, complete with the various accoutrements one might expect. Arguably, the performance went too far —that a professor would have their own private secretary is, at least in the cash-strapped UK context, nearly unthinkable. In its pretensions to being an established scholarly entity, Receptio made itself into a parody.

There is a legitimate question of whether the fabrication had an intent to mislead, to convince others that it had some sort of official status. As I have said before, it is not my purpose to untangle that issue, beyond saying that the controversy amply demonstrates how a modicum of internet checking could thwart any attempt by Rossi to fool: this was no elaborate scam worthy of the protagonists of Ocean’s Eleven. What I want to concentrate on instead is the allure of the ‘official’. There is a danger that the reaction in some quarters will be to assume we should only trust ‘real’ research centres, established by universities which, for their part, give due oversight and ‘quality control’. What might save us from taking that route is realising that Receptio’s fabrication is a parody of a system of higher education which is itself beyond parody. That academic system rather takes on the character of a set of distorting mirrors looking in on each other, the concatenation of which mis-shapes its intention over and over again.

Here my critique chimes with that of Charlotte Gauthier. This is a system in which universities — bodies whose charitable status mean they cannot make a profit — ache to ape the habits of commercial businesses, with the result that its students are demoted to the status of ‘customers’. It is a system that lives by the Research Excellence Framework (REF), where its ranking by stars is a sort of TripAdvisor for academe, but with the added demerit of misdirecting hundreds of thousands of pounds (not to mention human time) which could be better spent in supporting research. It is also a system that places high value on ‘grant capture’ — terminology that conjures images of funding as roaming the land ripe to be snatched by highwaymen-lecturers — and so requires substantial energy to be spent not on research but on hunting in search of the rainbow’s end. It is a system which has become a pastiche.

I am very aware that these comments will strike some as parochial. The structure of universities as charities is a particular British feature, contrasting to both the French republican tradition of their position as part of the apparatus of the state, and the American model where many are private institutions focussed on their endowment. I have talked to fellow academics in countries without a REF who wish they had one to tackle the problem of colleagues who spend more time building empires than engaging in research. I have also heard British colleagues say the REF is better than any alternative. It is certainly easier to diagnose ills than to offer solutions, and there is some comfort in hiding behind the mantra ‘I am not that sort of doctor’.

The comments are parochial in another way, one which reaches the heart of this controversy: they have intentionally concentrated on universities. Yet, all of us in established academic posts have a duty to remember that we are the lucky ones, however much at times we do not feel it. Lecturers and professors are not the scholarly community, they are one part of it. That community is enriched by the presence of librarians, archivists and curators, by ‘para-academics’, by those in short-term or part-time university employment, and by independent scholars — including the likes of both Peter Kidd and Carla Rossi.

Indeed, if there is a lesson in all this it is surely that those who do not have to follow the structures of universities should not feel the need to squeeze themselves into the painful strait-jacket. One interpretation of the Rossi affair (a generous one, I accept) is that Rossi felt she needed to don that strait-jacket, on the assumption that she would not be accepted otherwise. This is the most fundamental problem: to pretend that those in full-time permanent university roles are the only true scholars or even that they are inevitably the best ones. That assumption can create pressure for others to claim bona fides by appearing to be part of the university eco-system, and that is liable to create dubious practices. Perhaps, then, the hashtag Receptiogate, for all its unoriginality, has a use. If we read its last syllable anew, it can act as a reminder of the basic truth: beware of gate-keeping.

This is not to say that scholarship is a come-as-you-are, free-for-all party: it has its standards, and upholding standards is quite a different attitude from gate-keeping. One judges on the merits of what is written, the other uses proxies like employment status. Of course, there is an extra complexity: we each believe in our standards which we are determined should be upheld but, in truth, those norms of acceptable behaviour differ between and within disciplines; they are often defined by local tradition, or by generation, rather than by some translucent universal set of shared rules. There is no single habitus. If you doubt this, consider the range of practices used for citations with some willing to accept endnotes or even in-text author-date systems as ‘scholarly’. Perhaps, indeed, one of the attractions to some of the Rossi Affair was the belief that there had been uncovered a case of infraction of what (they assumed) was one of the few shared precepts of scholarship: you do not steal another’s work. Quite what constitutes plagiarism is a matter I want to discuss another day.

For now, my point is that the republic of letters has no generally agreed boundaries, just as it cannot have any centralised structure of authority, or border guards to police sanctioned crossing points. Gate-keeping is a problem because there are no gates through which to pass when entering this cluster of neighbouring — but often not neighbourly — communities. This lack of certainty is not a demerit; it is for many of us an attraction of this republic. It is also one which prides itself on not touching its forelock to status. There is admittedly much self-deception here as well as some continuing questionable practices: connoisseurship is out of favour, but the wider world still wants us to be able to express conclusive opinions ex cathedra. Whatever those continuing problems, it does mean that asserting status is not a route to acceptance as a scholar; on the contrary, it is symptomatic of the unscholarly — according to my standards, at least.

On the Receptio-Rossi Affair: a preface to some reflections

After the jollities, the hangover. Over the festive break, a corner of social media was abuzz with a tale of plagiarism, questionable business ethics and sloppy scholarly practices. It was played out in rapid instalments, on Twitter, Mastodon and Academia.edu. I refer, of course, to the concerns first raised by Dr Peter Kidd, beginning on 24th December 2022, concerning the Research Centre for European Philological Tradition (which takes Receptio as an acronym for its full title) and the recent work of its Director, Prof. Carla Rossi. The affair has been dubbed, in depressingly unoriginal fashion, #Receptiogate — when will we stop naming everything with a whiff of malpractice after a 1970s American political scandal? That said, perhaps the cliché in the name is to the point, given as what, in part, is at stake is unoriginality. The existence of that hashtag is evidence of how the first revelations about possible unacknowledged copying precipitated quite a Twittersquall, in which further allegations were levelled at Receptio. They must have made it a very un-merry Christmas in the Rossi household. To judge from Twitter, many would consider that fair comeuppance.

The affair is not over yet; at present, there is a counter-attack by Prof. Rossi, claiming she is the victim of hate campaign and hinting at dark forces at work. Meanwhile, Peter Kidd reported on 5th January that one of his blog-posts has been removed without his agreement. There is something unedifying about what is happening now but so there was also in the glee with which Twitter assumed there was a moral certainty of Good and Evil in a manner which exists only in second-rate Hollywood films. Like remembering the unwise actions of the night before, we might prefer to forget and move on from them. There is, though, a use to taking some time to reflect because it seems to me that it teaches us some uncomfortable truths about the state of the republic of letters now.

I should preface my comments with a statement of full disclosure. Of the two main participants, I have known one for over twenty years but not met the other once. I have read some of Peter Kidd’s work closely, having been the series editor for his catalogue of manuscripts of The Queen’s College, Oxford. We may have had our minor disagreements, which we have probably both now forgotten and they certainly have not dimmed my respect for his scholarly acumen. As to Carla Rossi, I am not aware of having come across her name before this dispute, though I have now heard positive report of her. It is my impression that some have, from the revelations of the past few weeks, drawn the conclusion that there has been a campaign to deceive of which the Receptio affair is only the latest instalment. I do not intend to attempt to assess the veracity of that assumption. On the contrary, I aim consciously to avoid taking that position, for two reasons.

The first is the basic emotional one is that I do not want something so depressing to be true. Watching the fracas progress, I found myself feeling a smidgeon of sympathy for a fellow human being and her family. Few find it pleasant to be under harsh scrutiny, particularly at a time which most take for recuperation. A desire to counter-attack and to deny any fallibility makes psychological sense but she should have been better advised. It must to be said that Prof. Rossi has done herself no favours. Her early reaction was to act with unbecoming hauteur about social media, belittling Peter Kidd as ‘un blogger’ (I will return to this in a later post), but saw no irony in posting that statement on her Academia.edu page. Her more recent pronouncements have rarely helped her cause. If this is the villain, they are not very good at that role; she has become too easy a target for it be useful to pile more pressure on her.

There is, though, a more important reason for my reticence. My concern is that pretending to moral certainty and identifying a villain is at best a distraction, at worst a serious misdirection. We might think that by isolating the one individual considered responsible for malpractice and shame them into ostracization, then we have done a good deed to save our system. But what is that system? That is the question which interests me more than the rights and wrongs of the actions of a specific individual.

I sense that a desire to consider the wider implications is already developing: witness Charlotte Gauthier’s useful post on the affair, the positive response that it has received. My intention is to expand on her thoughts and to consider three aspects of what is happening. The first will be what it tells us about the nature of the scholarly community or what we might call (reviving a noble Renaissance phrase) the republic of letters. That then leads us into the issues of how this republic communicates in this digital age. Finally, I want to reflect on the central issue at stake in this debacle: the nature of plagiarism.

What I will not be doing is providing a narrative of what has happened. That can be followed not just by reading the various blog-posts and social media feeds. Particularly detailed are Peter Burger’s Dutch language interventions (you can navigate to them from here). It will also be apparent that I am not intending to touch on the element which relates most directly to my own research, that is the opportunity the affair give us to reflect on the nature of fragment studies as it stands at present. This is a matter to which I want to return but, for now, I will confine myself to stating that I support what Lisa Fagin Davis has said about the deficiencies in what Receptio has produced.

A final warning: the posts that follow are merely first attempts to step back and reflect on what has been going on in this affair. There may not yet be the distance to do that with perspective, and the issues may need a fuller analysis than I can provide here. In an attempt to gain some space to reflect, I will not be posting them in quick succession but over a set of weeks. It is time, though, to provide the first instalment.

How to Research in the Online-Only World, the final part

The previous tip was a reminder that searching is in itself not enough – as early modern governments knew, effective record-keeping is essential to success. We talked about the methods of organising those records, with special consideration of reference management systems. There are two further tips that follow on from this.

You want your searching to be as efficient as possible. That does not mean narrowing your search terms – the implication of Tip I was that a sensible strategy is repeatedly to shift between different terms. It does, though, mean not having unnecessarily to revisit items that you looked at earlier, and so Tip VIII is: keep a note of your search history.

In many cases, this will be simple if you have a fit-for-purpose record-keeping. For an article or book, the bibliographical citation and the notes you make will be sufficient, though remember this: if you were to revisit that work later, having read other material in the meantime, you would be struck by other elements in it and different nuances. In other words, your reading is specific to that moment and that context — thus, a basic rule is to ensure you include in your notes the date when you came across that work.

For websites, of course, this is a standard expectation: a citation is not complete without a mention of the date of ‘last access’. That is because of the non-static nature of those sites, always capable of being updated. It is true that an increasing amount of online material is on ‘legacy sites’, ones where the funding (or the editor’s interest) has run out, and they have, in effect, become static. With those (and this is related to a point made in Tip III) you will want to make a note of when they were last updated. You will not need to return to those, but for ‘live’ sites, you may have to revisit them as they develop. The implication of this is that the tip could be rewritten: keep a note not just of your history but of your future, of those resources which you will want to check again before you finish your project.

This may sound like a demonstration of the truth of the Old Testament verse: of making many books, there is no end (Ecclesiastes 12:12). You may feel that to be particularly true in recent months, in the lockdown and its aftermath. There will be many resources that you know are themselves locked away in libraries or archives to which you cannot gain access. Tip IX relates directly to those: do not shy away from recording the material that is, at present, not available.

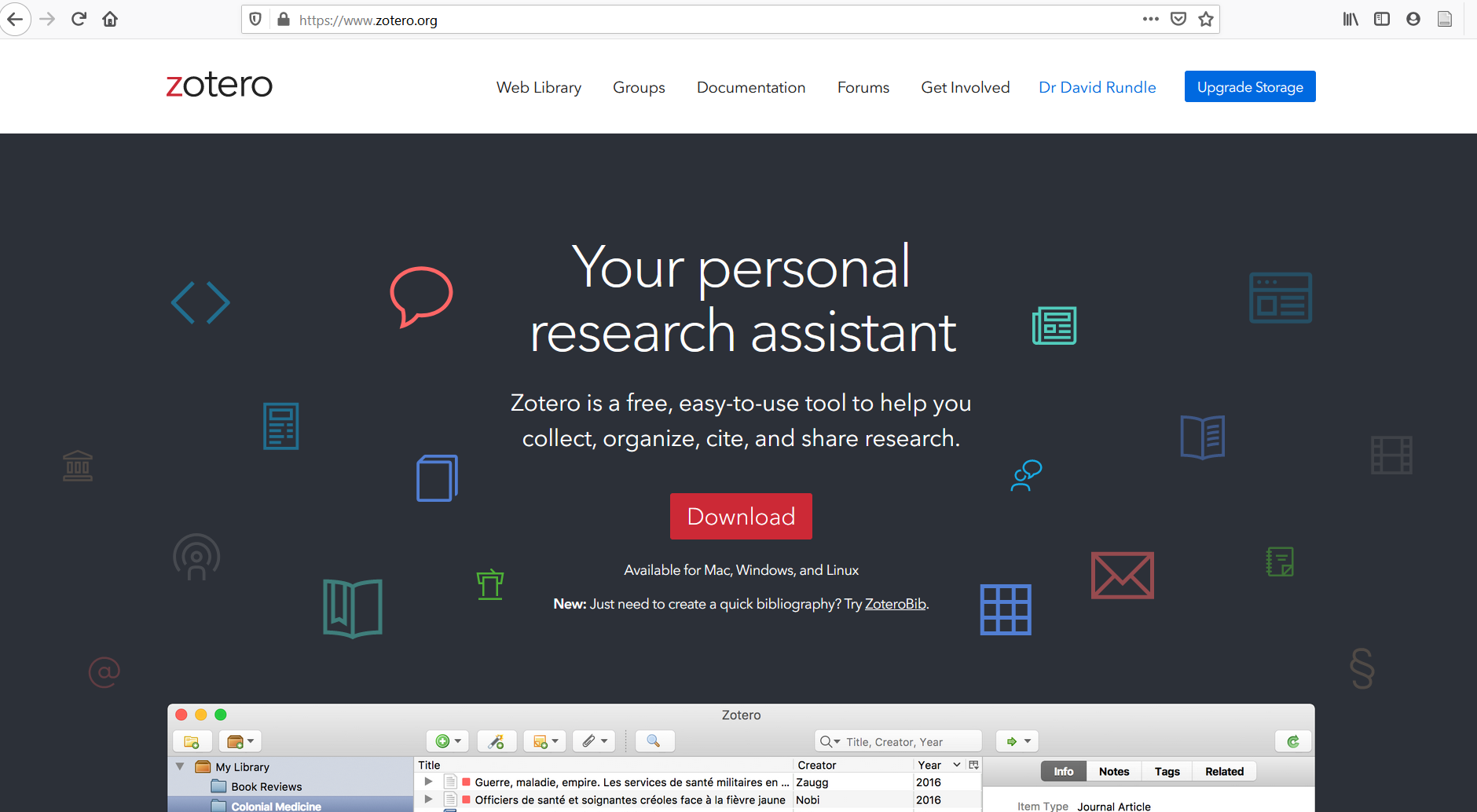

You will, of course, need to make a note that you have not been able to see it (in a Word bibliography, I mark an entry with an asterisk when I am yet to consult it; in Zotero, I add a reminder in the note field). You will then wonder what to do about something you cannot see. The question you have to ask yourself — and your supervisor or mentor — is: how essential would this work be for my project? If the answer is that it is truly crucial, it may be that you will need to reframe your investigation in some way. It is true that, in the present situation, many institutions are taking into consideration the difficulties of access when marking, particularly at the undergraduate level. Yet, let us be honest, you would not have got this far in reading these tips if you would be satisfied by writing something which is ‘good enough, in the circumstances’; you want to produce a work which is as good as humanly possible. There are always constraints — the amount of time and the number of words available being constantly two of them. We are working with another, temporary one but we are not just working with it, we are also finding ways to work around it. This brings me to the final tip in this series and perhaps, in our present context, the most important one. Tip X can be summarised in one word: share.

Research is a lonely business. In the humanities, the process is, on one level, unavoidably isolating: you work away with your primary sources and secondary material, making yourself into the one expert in the world on your particular niche, gaining a depth of understanding and (hopefully) an enthusiasm that to others can be frankly perplexing. One talent any academic has to develop is how to convey that knowledge and excitement in a way that is not only clear to others but also helps them share the fascination. The methods we have to do that, through seminars, workshops and conferences, have had to be re-designed for this Covid-19-infested world. I am sure we all cannot wait to be able to engage with people in person, but we also do not want to lose what we have gained during this period. For, there have been benefits: many people — particularly students — have shown a resourcefulness and a collegiality which is impressive and deserves to be kept alive. There have been excellent initiatives from York’s ‘lockdown library’ to Canterbury’s MEMSLib. The latter brings together both some useful (and growing) pages providing listings of online resources with a forum that allows researchers to make specific requests. The site has been designed and created by a group of students — MA, PhD and post-doc — whose passion is equalled by their industry and intelligence. They are responsible for many of the listings, but they have also brought in colleagues (young and, in my case, not any longer) both from Kent’s MEMS and further afield. It has shown how a community can put aside hierarchies and work together to produce something which is of immediate but also lasting benefit. In doing this, MEMSLib and other initiatives like it have shown how we can make social distancing sociable.

So, I ask that you share in a double sense. First, do not suffer alone. If you cannot find a specific work or need help with a particular element of your searching, ask — ask your friends, those you know in your institution or a resource like MEMSLib. Equally, share what you have. I have heard of students offering to send their peers books in the post; I certainly have fielded queries from colleagues across the UK wanting a reference checked in a book I happen to have on my shelves. I have also been grateful for those to whom I have sent unsolicited emails asking for their articles, all of whom have responded generously. These acts make our lives as researchers somewhat easier at this time. They matter because the little kindnesses are a model of how a scholarly community should be — our own new republic of letters. They matter for us as seekers after arcane knowledge but they also matter for our humanity.

How to Research in the Online-Only World, part VII

The previous tip, like the others so far in this series, was about how to make your searching as successful as possible. That, though, is not enough. The fuller your set of results and so the longer the bibliography, the more the challenge of ensuring you can refer back to specific items in what you have found. You need to be able with ease to gather together all relevant material on a particular element of your research. This means that Tip VII is: at an early stage in your research, work out how you are going to store your results.

Allow me to begin with a recollection of my young self’s odyssey through the bookshelves. When I began my undergraduate life, I took notes on lined pages of A4 (as many students still do). In my final year, I started to stumble across articles in a library or a seeing a volume in a bookshop when I did not have a notepad with me, and so wrote on any scrap of paper that was to hand. I assumed I would write up those scribbles but it never happened and I came to realise that these were not a preparation for more formal notes, they were my notes. So, I ordered them by date of writing in A5 ring-binders and, taking some discarded catalogue cards (this was the age when libraries were throwing them away as they computerised) I created an index for them. I have not added to them for many years now —nowadays, I am more likely to send myself an email or take a photograph — but I do still refer back to them.

I tell this tale to highlight several related points: your habits can and will develop organically but there is a time when you will have to develop a strategy for your research notes, and that strategy will need to consider both how to organise them and how to make sure you can refer back to the information you want, not just now but potentially much later.

Therefore, decide what is going to work best for you. You might be inclined to produce your notes long-hand and, as an old-style manuscript-over-print person, my instinct would be with you but I have to ask: is that wise? Will you have the time to convert your handwritten records into typed citations as you complete your project? Remember that the so-called Parkinson’s Law (work expands to fill the time available) is an exemplum of understatement: work gorges itself and becomes so blotted that even if time doubled, it would not be sufficient to accommodate it. If, then, you might be best advised to put your pen aside, there are three possible solutions:

- Word document — the simplest option but also a serviceable one. It requires you to be confident in how you cite a work, but that is a good skill to have. You can enhance its usefulness by using the link function (in the Insert menu) to associate an entry in your bibliography with a file in which you have taken notes from that article or book (just avoid later having a spring-clean in which you rename the files and so break the links!). You would need to think about searchability but that is a point we will discuss in a moment.

- Database — most people avoid using Microsoft’s Access which seems to be the most unloved of their Office suite, and few pay for and build their own database in something like Filemaker. Instead, there is a tendency to use Excel as if it were a database, and that can work. The problem with this solution is twofold. First, there is the issue of ensuring accurate and consistent formatting in a program which is not designed to be a word processing application. Second, there is the matter of converting the fields into flowing text if you want to download from it to create a bibliography or citations.

- Reference Management Software — to avoid the issues just mentioned, several pieces of software have been developed precisely to help with storing the information you gather. There is a long list of possibilities but I think it is fair to say that there are four which are best known (listed alphabetically):

You might already have your own preference for another, and feel free to declare that in the comments. Some might suggest, for instance, Paperpile, but that is designed to be used with Chrome as its browser, so if (like me) you are committed to Firefox, it is not the one for you. Between those mentioned above, there are two major differences: some are particularly designed for collaborative work as is common in the sciences (EndNote, Mendeley); and — here is a more fundamental consideration — the first two cost while the second two are freeware. It is true that many universities have an institutional subscription to one of the commercial programs (at Kent, it is RefWorks); you may, then, want to accept that option, but bear in mind the issue of how you would export your files when you leave the institution.

Of the ones listed, I have only used EndNote and Zotero. From my experience, they have similar strengths and also weaknesses but of the two I would always recommend the free option. That is not because I am a cheap-skate (not solely) or virulently anti-capitalist (though we all have a duty to tackle the injustices in the system) but because commercial software can disappear more easily and freeware has a greater chance of future compatibility.

The advantages that all these programs claim is that you can download references directly from the web and that you can then export the citations you want in one of a range of standard formats. Neither of these features should let the user imagine that they need do nothing: to make the most of them, your involvement is required. The bibliographical formats include MHRA, which tends to the basis of most humanities citation systems (despite its infelicities, like including both publisher and place of publication — a waste of space, in my view) but each institution can require slight variations, so this does not do away with the need to check through your bibliography. More significantly, the download feature is not a fail-safe. You will come across mentions of works you want to list which are embedded in a text and so cannot be identified by the application. You will need to type or cut-and-paste. On this point, one minor irritation is that none of the software I have used has short-cuts for accents, so if I say, I wanted to include a work by the early twentieth-century British medievalist, Charles Previté-Orton, I would need to type his name in Word and transfer it from there. A more important issue is the download can be wayward: it sometimes does not recognise a site as giving an information about a book and so will download it as a webpage, without publication details. Personal intervention is needed here and that is not the only place it is essential: publishers might provide their publications with a list of tags but they are usually generic and you will want to do better than that.

This brings us to a key piece of advice: recording what you have found in a consistent way is not enough; you need to ensure that the entries are as searchable as possible. This is why you need to think about keywords or tags. In Zotero, the software’s search function covers everything: the titles, names of authors, abstracts and any notes you add. You may think that is sufficient, but, if you are using such a form of reference management, do make use of its built-in facility for tags; if, instead, you are using a Word document, you will want to remember to add keywords to each entry. What is important is not simply to add them but to be consistent in how you do it. You do not want to find that information is unfindable because you have shifted in your spelling or in the conventions you use (do record ‘15th century’ or ‘15th C’ or ‘C15’ or ‘s. xv’?). You may even want to establish a file where you make a note of the conventions you are using — though that is a counsel of perfection which I myself have not achieved yet. What you may find useful is to think through how you have constructed search terms in Google, as discussed in Tip I, and use that process as a guide to how to create your own system of tags.

In summary, then, the advice is to develop early a programme of what program you will use, then commit to it and make it work for you by using all the features and the latitude that it allows you. There are further tips that follow on from this, which will be the subject of the next post.

How to Research in the Online-Only World, part V

The use of periodicals was central to the previous tip. Many engage with recent scholarship through reviews or review articles (the difference being that the latter bring together several publications to draw out comparisons and shared themes); some journals, however, do not have a review section. What they all share is that they publish fresh research in the form of articles, usually around 8,000 words, but some journals allow more extensive discussions, while some also includer short notes. So, the latest tip is, put simply, check regularly periodicals, but not just them — do the same also for publishers’ websites.

You might think that if you want to know what appears in a journal, you will simply go to JSTOR. If only it was so easy: that website is a rich resource but, for the vast majority of leading publications, it does not have the rights to the most recent issues. As, then, you want to know what is at the cutting-edge in your subject, and you know you are not going to find that via bibliographies or by JSTOR, you will want to check relevant periodicals. Some of them help by emailing out the table of contents to each issue (e-TOCs). So, it is worth making yourself a list of the major journals, and, where possible, signing up for their e-TOCs. Increasingly, though, journals are listing forthcoming articles or giving some limited access to them by ‘early view’ (Renaissance Studies is an example of this). So, bookmark their pages and check them regularly. Some journals in the list below are annuals, but most publish more frequently (some twice, some four, some five) times a year.

Below I list some examples of leading journals, to which I frequently return for their articles and (where they have them) their reviews. In addition, I list some major academic publishers. That is because, if you want to ensure you are up-to-date with the very latest in your particular topic, you will want to be sure you know what is being published in the form of monographs or collections of essays. Some periodicals might advertise some of these, but the best way to reach them is, as with journals, to visit regularly and look for latest publications on these websites.

So, here are my personal and very selective lists of ‘go-to’ journals and publishers. The selection of periodicals is divided into three, reflecting some of my areas of interest (I omit manuscript studies and the history of the book, because my suggestions for those will appear on the MEMSLib website). The sections are (a) Medieval, (b) Renaissance and (c) History.

1. Medieval

Speculum — the journal of the Medieval Academy of America, published by the University of Chicago Press.

Mediaeval Studies — the Canadian riposte to Speculum, this annual is produced under the aegis of the Pontifical Institute in Toronto. It carries editions of texts and articles, mainly on historical and literary themes.

Viator — a third important North American journal is produced by UCLA and has a special interest in trans-national topics.

Traditio — another major US journal of medieval studies, this annual (with no reviews) is from Fordham and its main remit is intellectual history

Medium Ævum — the remit of this British journal is hinted at by the name of its publisher, the Society of the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature (who are worth checking for their events, grants and essay prize).

2. Renaissance

Renaissance Studies — the publication of the British Society for Renaissance Studies, this is broader than its name suggests, being particularly strong in early seventeenth-century English literature.

Renaissance Quarterly — the American equivalent of Renaissance Studies but with more focus on the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, and with an extensive review section in in each volume. It is published by the Renaissance Society of America, who also organise the world’s largest (indeed, outsize) annual conference on the Renaissance topics.

I Tatti Studies — published by Harvard’s I Tatti Center, situated outside Florence, it concentrates on the Italian Renaissance.

Rinascimento — as its name suggests, Italian is this journal’s first language but its remit is not confined to the Renaissance in Italy.

Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes (known as JWCI) — do not tell the Warburg Institute that their annual is about the Renaissance! They insist it is much wider than that and it certainly is but it does frequently include important articles on Renaissance themes (in the latest issue, for 2019, five of the eight articles are relevant). JWCI does not carry reviews.

3. History

English Historical Review (known as EHR) — particularly associated with Oxford, this has traditional strengths in medieval history, though it ranges much more widely.

Historical Journal (known as HJ) — this is associated with Cambridge, and tends to see history as starting in the fifteenth century.

Transactions of the Royal Historical Society — the annual periodical, as its name suggests, of the Royal Historical Society. It concentrates on articles that began life as lectures and has no review section.

Past and Present (known as P&P) — like EHR, published by Oxford University Press. It sees its particular remit as social and intellectual history, and in some ways as a British riposte to Annales.

Annales — perhaps the world’s most famous history journal because of its association with a particular French ‘school’ of historical study, it now appears in English as well as French.

Of course, there is a balance: the broader the remit of a journal, the more prestigious it may be but the fewer the articles it will publish that will be relevant to you. At the other extreme, there are a plethora of publications which are more specialised but usually have a lower academic standing. That does not mean you can ignore them: if they are germane to your topic, it is important to know what they are publishing. These journals might be defined by a relatively narrow time-period (The Sixteenth Century Journal, for instance) or by a regional focus (Archaeologia Cantiana for Kent is a good example) or by affiliation to a cause (The Ricardian was set up by partisans of Richard III against his detractors, but it does now include important scholarly articles).

What all these will provide is insight into what are the ‘hot issues’ in your area, but they do not stand on their own. Alongside these, it is important to be abreast of what is coming out in book-length form, and for that, it will be useful to check what relevant publishers. They divide into three: your first port of call will be the big University Presses, both in Britain (Cambridge and Oxford but also Manchester) and in the States (Yale, for instance, has a high reputation for its books in art history). Second, there is that noble subset of commercial publishers who are willing to commit to scholarly monographs: in Britain, for medieval studies, Boydell and Brewer has a deserved reputation, and their catalogue includes series like York Medieval Press and King’s College London Medieval Studies; across the Channel, in Belgium, a similar service is provided by Brepols (which we mentioned in Tip III). Then they are the learned societies who act as their own publishers of monographs: two with which I have had dealings are the Society for Study of Medieval Languages and Literature (already cited for its journal) and the Oxford Bibliographical Society, which has a fine line in manuscript catalogues.

You may now want to rush off to look at all these websites but feel frustrated: you can find titles and abstracts or publishers’ blurbs for recent items but may not then have full access to them if your institution does not have a subscription. What are the ways around that? We will return to this in the last tip but there is also relevant advice in the next one, Tip VI.

How to Research in the Online-Only World, part IV: the value of reviews

No grand plan (or even not-so-grand) that one conjures up in the mind’s eye ever unfolds in this benighted world quite as you expected. I have been holding back on publishing this latest instalment in the short series of ten tips for academic searching online. That is because I was anticipating quickening the pace and publishing a few tips together but that will have to wait. As I drafted the advice for each, the text has grown. So, we are going to continue as we started, with one tip per post for the next few days. As a result, today we have Tip IV which can be stated simply as:

Trawl Reviews

In the previous post, we noted that both the use and the limitations of bibliographies. One necessary method for supplementing them is by trawling through reviews of recent publications. Checking bibliographies and reviews have complementary strengths, but also share one main drawback. While bibliographies are most helpful in alerting you to articles in journals or collections of essays, reviews focus on whole volumes, whether they be essay collections, monographs or editions of texts. The advantage of reviews is that they engage with the works they are discussing — the best give an overview of its contents, place it within wider scholarship, and give an assessment of its quality. Sometimes, they can be openly hostile or simply bitchy, but in most areas that style has thankfully gone out of fashion. The result, though, is that there is an art not only to writing reviews but also to reading them (certainly, if you encounter one of mine, you are encouraged to read between the lines).

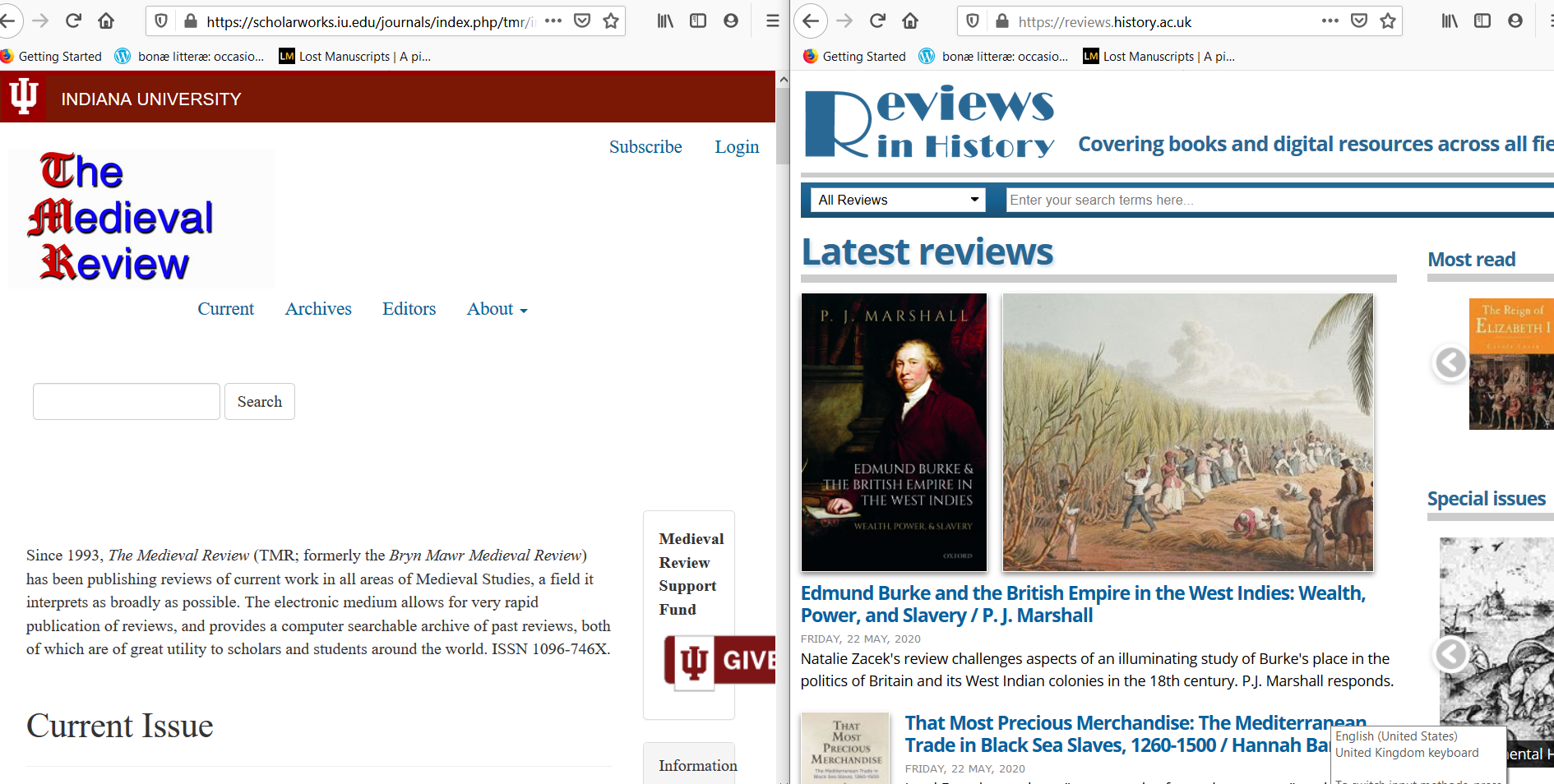

There are nowadays some online publications which are dedicated to providing reviews. I will give you two examples, to which I have signed up for updates and which are likely to be useful to medievalists or early modernists:

- The Medieval Review – once known as the Bryn Mawr Medieval Review (and so the sister of the Bryn Mawr Classical Review, which sometimes has discussions of post-classical works discussing later traditions informed by the ancient world), it has moved allegiances and is now under the aegis of Indiana University

- Reviews in History – run by London’s Institute of Historical Research; its main focus is on later history (compare the 452 reviews falling within the millennium and more designated as ‘medieval’ in comparison to the 1172 for the twentieth century) and so earlier coverage is patchy but still useful

You may well have other suggestions, and do add them in the comments. For now, here are a few pointers for using them:

- A review tells you about more than just the book it names — as it will place the volume under discussion in context, it will allude to other relevant scholarship. Sometimes this will be provided only as a set of surnames (reviews rarely come with footnotes) but they are valuable leads for you.

- Think about the author of the review — ask yourself what they may have written which is relevant to the topic. The immodest will cite their own works; those who are yet more arrogant will expect you to know. For either of these types of reviews, you will want to investigate their profile further, and on that we will give advice in Tip VI. Others may be too early in their career to have published on the subject (most scholars first publications are reviews), but it is still worth trying to learn something about them as you develop a sense of the community who work in areas allied to your own.

- Check relevant journals — as well as the online only platforms, most (but not all) academic periodicals have a review section. We will talk more about journals in Tip V. At this point, it is worth noting that some journals, as a taster, put online and free of charge some of its reviews before they are published in hard copy.

- Reviews are of recent works, but not that recent — if you want to cause one of your lecturers maximum discomfort, ask them how many books they have on their shelves for which they still have not submitted their review. Even when a review has been submitted, it can take several months before it appears in a journal (the turn-around is quicker in the online-only world). As with the bibliographies we have discussed, there is a time-lag between publication of the work and it being noticed in academic publications. Some periodicals appear more frequently and try to be quicker — I am thinking of the Times Literary Supplement and the London Review of Books — but even then they tend to run their reviews more than half a year after publication, they sit behind a paywall. Do not worry too much about such ‘literary reviews’: as they cater for such a broad audience of literati, the number of articles that they publish which will be relevant to your research will be small.

The upshot of these observations is that, while reading reviews are essential addition to searching bibliographies, it is not going to give you access to the very latest published research. That is the topic of the next tip.

How to Research in the Online-only World, Part III

In the previous posts, we have discussed the most basic tools for searching, Google and Wikipedia. In this instalment, we move beyond them and look at some resources which are more specific to those of us who are medievalists or early modernists, though the lessons we will draw still have wider relevance. Tip III is a very simple one: use bibliographies and portals.

The term ‘bibliography’ is used by academics with two separate meanings. It can signify the noble scholarly tradition of describing the material book but it can mean the useful practice of listing publications on a topic. It is works in that second category that we are going to discuss here. Works of this kind became a common resource in the print world of scholarship, and some witnesses to that can be partially viewed online: to give just one example, Google Books has The New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature, with its first volume, edited by George Watson and covering a millennium from 600 to 1600, published in 1974 (‘New’ because it superseded a previous version, published in 1940). Books like this were, of course, becoming obsolete from the moment of publication, becoming more out-of-date with each passing winter. In some areas of study, they could be supplemented by annual reviews: for instance, The Year’s Work in English Studies, first published in 1921, or the English Historical Review’s summary of periodical articles which appeared in the previous year. These continue to be produced and are very useful (and sometimes mischievously entertaining). In the hard-copy world, however, if you want to check what has been written on your topic over a set of years, you would need to take a set of them off the shelves and check through them methodically. This is to say that such bibliographical ventures were created waiting for the internet to happen.

The online world was made for searching, though as we are about to see, you must develop a range of tactics and techniques to make the most of the bibliographies and portals that are available. Here is a very short list of useful resources for medievalists and early modernists:

Bibliographies of published works:

- Oxford Bibliographies — this resource covers many fields, but it is mainly two that are relevant: ‘medieval studies’ (but that does not include ‘medieval manuscripts’, which are in ‘art’) and ‘Renaissance and Reformation’). This is a commercial resource but some of the entries are freely available

- Regesta Imperii — the most expansive free bibliography of the Middle Ages

- Brepolis – so-called after the Low Countries publisher, Brepols, this includes a suite of databases, the most relevant: the International Medieval Bibliography (IMB), the Bibliography of British and Irish History and the Bibliography of Humanism and the Renaissanc

Portals listing relevant websites:

- The Labyrinth — a collection of online resources for medieval studies, compiled by Georgetown University

- Early Modern Web – run by the scholar of early modern crime, Sharon Howard. This includes Early Modern Commons, a listing of relevant blogs (with a search function but one, note, that searches by tag, not by full text of the blogposts themselves)

Let us compare the bibliographies just cited by setting them a task. The person I have chosen for this exercise is one of the leading humanists of the earlier fifteenth century, Guarino da Verona.

Guarino da Verona (1373-1460) as depicted in a medal from the early 1440s by Matteo de’ Pasti

He receives a short discussion in the Oxford Bibliographies, which concentrates on the classic studies of his life. A different approach is taken by IMB and the Regesta which both focussed on recent publications. If you type ‘Guarino da Verona’ into IMB, the search returns 12 results (gratifyingly including an article of mine); in the Regesta, there are 13 entries for him, but not including my piece (shame!) and, in fact, with only one work overlapping between the two lists. These numbers seem rather low for a figure of Guarino’s stature and, indeed, if you change the search term to the version of his name more often used in present-day Italy, ‘Guarino Veronese’, you are landed with many more hits: IMB gives 102 results (including the 12 mentioned) and Regesta 59 (not overlapping with the 13 previously mentioned), with only seven items appearing in both. If we return to Wikipedia, the English article on Guarino includes no citation of scholarly significance, but the Italian one adds a few articles, none of which appears in either of these databases.

So, what lessons can we draw from this example? I want to highlight five points:

- You cannot rely on one single bibliography — as this test-case shows, neither Regesta or IMB can claim to be comprehensive. It is important both to cross-check between them and to be aware that there will still be more items to find. To put this another way, a search strategy that relies on a single resource does not deserve the name of a strategy. We always have to learn to move between several sources of information, with the ones we employ changing according the specific topic we want to investigate.

- Understand any database’s limitations, both intended and incidental — you might be wondering why no bibliography is entirely complete: that is a good question and one you should always ask yourself. Before you begin using a resource, you should read what it says about itself to understand its self-imposed limits. Then, as you use it, you will develop a sense of its strengths and its weaknesses. There is a fundamental principle at work: behind every screen sits a human being or, in the case of major projects like IMB and Regesta, a whole host of other humans. They rely on contributors, some of whom will be more efficient than others. The resources also develop within particular academic traditions: IMB is led by Anglophone scholars and, through its Brepolis sister, the Bibliographie de Civilisation Médiévale, links to a French équipe; Regesta Imperii has an English search function but is designed by German-speaking academics. The regional focus of each is one partial explanation for their differing coverage, though another important one is simply that they look in different places.

- The further back an online bibliography goes the less reliable it is — one limitation both the databases discussed share, and one which is common in digital resources, is that, in their concentration on more recent publications, they are less full for the older literature, even when that remains foundational. For my chosen topic, the most important studies continue to be those written at the turn of the nineteenth to twentieth centuries by Remigio Sabbadini: Regesta does list some but not all of them, while IMB has none (the earliest entry is from 1965). These older works are, of course, easily discovered by reading more recent discussions, including standard biographies (in this case, the best being that in the Dictionary of Italian Biography, DBI). Once more, though, the moral is: use many resources in concert together.

- Check the date of compilation — at the other end of the chronological spectrum, there is always going to be a cut-off point for inclusion. If you look at any Oxford Bibliography, it gives at the top the date of latest revision; anything published since then will not be included. The main databases do not state the date for the latest uploads as they aim to be up-to-the-minute but do not be fooled: there is always a lead-in time and they are not the place to find the very latest word on a subject (we will discuss that in the next couple of tips).

- Use variant search terms — this example also gives us an opportunity to reinforce one of the very first pieces of advice given. Do not confine yourself to a single version of the name or term you want to investigate; you will miss relevant results if you do not think of different permutations, so use them too.

Of course, the advice here does tend to require us to include in our research bibliographies which sit behind a paywall. You might understandably wonder how that is possible if your institution does not subscribe. I will return to this in the last tip but, for now, let us reassure ourselves: if you are connected to a centre like Kent’s MEMS, you are part of a supportive community; ask us, and we will do all we can to help.

How to Research in the Online-Only World, part II: not so wicked Wikipedia

In the first instalment of these ten tips on researching online, we talked about what you need to do before you start searching online. Today’s suggestions are about what will happen when you type your first query and press enter. Tip II can be summarised as: do use Wikipedia as a springboard for your research.

It is everywhere: you open your browser, you provide a search term, and, in most cases, one of the top results will be a Wikipedia entry. We all know that the world’s favourite online encyclopaedia is not to be trusted – they tell us so themselves – but it is also unavoidable. The sensible approach, then, is not to pretend it does not exist and to move on to the next hit but to read it conscious of its quirks and limitations. This, of course, is what we must do with everything we read, but Wikipedia has some particular difficulties — as well as some advantages.

In a schema popular in the US, Wikipedia constitutes a ‘tertiary source’, that is something which is not a distillation and interpretation of the primary evidence but a distillation of those distillations (which are termed secondary works). In this tertiary category sit all reference works. What marks Wikipedia out from all encyclopedias is its policy that anyone can edit it, and that is often seen has a cause for concern, a sort of worry about what happens when you let non-experts loose. I have suggested in the past that this principle does not, in fact, make it inherently any more unreliable than traditional encyclopaedias. The observation I made some years ago still holds true: the better-known concepts and characters might receive attention from editors who are more opinionated than well-informed but, if the subject is relatively obscure, Wikipedia is sometimes a fuller and more helpful resource than other encyclopaedias, which would give the topic at most cursory attention. That is because, for those articles where few people bother to make a contribution, the ‘anyone’ who provides the information is likely to have a scholarly interest in the subject — like, for instance, being someone who has written their MA dissertation on it. What I will say has changed since I made that observation is that some of the larger articles have become more shapeless: text tends to accrue rather than be deleted, with the result that it can read as stilted or even self-contradictory.

The implication of what I have just said is that there is wide variation in the quality of articles in Wikipedia. So, how do you decide whether the piece you are reading is a stinker or not? Here comes the first piece of advice:

- Scroll to the bottom — after all, it is the section called ‘References’ which is going to be most useful for you, letting you move away from Wikipedia to other resources. Look at this section and ask yourself two questions: how up-to-date are the works cited? Are they scholarly? The first of these, which (as we will see in Tip III) is a question you should regularly ask, is straightforward: look at the dates of publication. The second may need a little explanation: while it is not always an accurate guide, where something is published may suggest its scholarly worth. Being printed in an academic journal or a university press is no guarantee of quality, but if what is being cited is (for instance) a newspaper or a commercial site, alarm bells should ring. As an example, let us look at this article about an academic playwright and author from fifteenth-century England.

The text looks fairly full — this is not what Wikipedia calls a stub — but look down to the ‘attribution’ and ‘references’. The attribution explains that part of the text has been imported from the Dictionary of National Biography (universally abbreviated to DNB). That was a worthy reference work at the beginning of the twentieth century (the article used was published in 1901) but it has been superseded by the more recent, rewritten Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (abbreviation: ODNB). You can check how much has actually been imported from the DNB, because the original text is available on another wiki site, Wikisource. If we now look at the references cited on the Wikipedia page, they do not suggest that article has been substantially supplemented. The first is to a German reference work, while the second comes from a scholarly journal, but it is a review of a 1970 edition of a play of Chaundler. Reviews are not something you would usually expect to find cited in a scholarly work — they themselves are ‘tertiary’ in the sense that they mainly comment on others’ work with the primary evidence. This Wikipedia page is, in fact, so indebted to ‘tertiary sources’ that it could be called quaternary.

The text looks fairly full — this is not what Wikipedia calls a stub — but look down to the ‘attribution’ and ‘references’. The attribution explains that part of the text has been imported from the Dictionary of National Biography (universally abbreviated to DNB). That was a worthy reference work at the beginning of the twentieth century (the article used was published in 1901) but it has been superseded by the more recent, rewritten Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (abbreviation: ODNB). You can check how much has actually been imported from the DNB, because the original text is available on another wiki site, Wikisource. If we now look at the references cited on the Wikipedia page, they do not suggest that article has been substantially supplemented. The first is to a German reference work, while the second comes from a scholarly journal, but it is a review of a 1970 edition of a play of Chaundler. Reviews are not something you would usually expect to find cited in a scholarly work — they themselves are ‘tertiary’ in the sense that they mainly comment on others’ work with the primary evidence. This Wikipedia page is, in fact, so indebted to ‘tertiary sources’ that it could be called quaternary. - Understand how the page has come to be how it is at the moment — the citations each page provides help you gain some sense of how much trust you can place in it but you can go further. Look to the top of each article and you will see some tabs. To the right, just left of the search box, there is ‘view history’. Click on this and you can trace through the editing process. Wikipedia is an encycolopedia that lets you see its workings in a way no other would. You may not, however, find that listing of edits, scintillating reading. For something more informative, go to top left, and next to ‘Article’, you will see ‘Talk’; click on that and you will see discussion betweent the various contributors about how to improve the article. These are most entertaining when dealing with a controversial figure, like Richard III. The entries reveal how repeated and valiant attempts have been made to save the page from the immoderate partisanship of that monarch’s latterday supporters. It must be admitted, though, that they have not managed to delete the clanger of a statement that the Battle of Bosworth ‘marked the end of the Middle Ages in England’, as if one August afternoon in 1485 was when the light-switch was flicked from darkness to modernity. Leaving that aside, what the ‘view history’ and ‘talk’ tabs do is let you understand how a page has come to be as it is, and return in a few days or weeks and you can see how it has changed again. So, if an article does not read well, look to these sections to appraise how that has happened.

- You will need to verify what you read — it is an article of faith among historians that we trust no one, not the writers of the primary evidence nor the scholars who have gone before us. But Wikipedia requires particular care. Remember: it has a policy that no original research should be included on its pages. So, in every case, ask yourself: from what secondary work did they get this information? Here the references and external links will help. You will want to check them to find out on what basis they make a claim that has been repeated here.

- Remember that Wikipedia is not one encyclopedia but several — it exists in a wide range of languages, including (I am pleased to say) in Latin. The crucial point is that the articles are often not simply translations from one tongue to another but are largely independent of each other. Some of you might say: what use is that to me when I only read English? Don’t worry, you have time to learn more languages. For now, though, if you only read one language, it is all the more important that you check the other versions: if you are thinking of a research topic and find there are major works on that subject in another language, you may want to think again (or start learning the language straightaway). And you do not need much linguistic knowledge to navigate a Wikipedia page because they are all laid out in the same way. So, scroll down the left-hand side of the screen and you will see that the last section is entitled ‘languages’: click on those to find what is being said about your intended subject in other countries.

- Think of editing Wikipedia yourself — you must not take the democratic principle that anyone can edit the online encyclopedia to mean ‘anyone but me’. As you develop your knowledge, you are likely to be able to make valuable improvements to a page. Do not be a passive recipient of knowledge, be one of its creators. There are already some people in MEMS who do it: join us.

The wording of this tip is not my own: it is Wikipedia’s. They do not expect you to rely on it unthinkingly. The main advantage it has for you is that it can lead you to other sites and materials. It can help you begin the virtual paper-chase that is building your bibliography — and that will be the topic for the next instalment.

How to Research in the Online-Only World: ten personal tips, Part I

This lockdown is a child of the IT revolution in which we are living: the way we are Skyping and Zooming and Teams-ing through it would have been unthinkable twenty years ago, even perhaps ten. At the start of this century, though the internet search engine was a known phenomenon, Google had not yet been launched. Now, when we are stuck indoors, it is our doorway to the world. We are all living through our computer screens.

There are, of course, many anxieties and worries caused by the ‘new normal’. In the scheme of things, what follows may seem minor but, for one small section of the population, a particular frustration of the lockdown is the lockout from the libraries. For the duration, I am seated two miles from one of the world’s greatest collections of manuscripts and printed books, and I cannot touch any of them. In this situation, all of us who do research — be they undergraduate dissertation writers, MA or doctoral students, early career scholars or those later in life like myself — are having to reshape how we do our most fundamental work, and learn what it is to study without the physical book.

Some of the responses to the situation have been heart-warming: library staff are working hard to help readers gain access to material even while their doors are closed; through social media and email, scholars have come to the support of each other. I am very lucky to be part of a convivial and helpful community at Kent’s Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Some of its graduate students, building on good precedents elsewhere, are building a lockdown library so that they can help each other as they continue to research in these unexpected circumstances. Part of what they are doing is gathering together information about useful materials that are available online and providing helpful listings: at this time, necessity is proving the mother of inventorising.

It is in the same spirit that I thought it might be of assistance if we reflected on how we research a topic online and can use our experiences to perfect our techniques. I have come up with ten tips which I will share with you over the coming weeks, in the hope that they will help stimulate a conversation. The audience I have mind is, in the first place, those who are in a similar situation to our MA students in MEMS, but what I have to say should also be relevant to undergraduates starting a dissertation, and perhaps will not be entirely tedious reading for those more advanced in their research. It is also worth emphasizing that these tips reflect my own disciplinary background as an historian and palaeographer, and my chronological focus in the Renaissance, spanning the later Middle Ages and the (early) early modern period. In short, there will be much you can add to what I say and I welcome the opportunity to read from you.

Today, Tip I: Define and refine your search terms.

You have a sense of the topic you want to research and you want to narrow down its focus, check its feasibility and build up your bibliography. You are sitting in front of your computer screen with Google open and you are ready to type. The first tip is: stop, get a piece of paper or open a Word file. What you want to do is to think through what search terms will help you get the best out of the internet. If you are studying a particular character or text, you might think that is straightforward. However, if you just use the name and that person or work is very well-known, you will overwhelmed with the results: type in ‘Henry VIII’ and it returns 179 million results; Hamlet and you get 108 million. Yet, you will not be writing the king’s biography or a summary of the whole play, so you already will be thinking of the first wise step:

- Break down — many of us may feel like doing that at the moment but I do not mean you personally (and if you are feeling worried, do call for help). Instead, break down your topic into its elements, or think of identifiable individuals who will feature within it, characters who are less well-known and so you will receive a more manageable set of results. Similarly, you could search for a specific event which is within the remit of your topic. Go small.

- Remember the basic tricks of searching: for instance, try putting a specific phrase within inverted commas.

- Likewise, enter terms no prepositions — the absence there of ‘with’ makes it ungrammatical, but Google speaks a different language from mortals: you will gain more focussed results by leaving out the little words.

- Use variant spellings — let me give an example from my own research. One central figure of my studies is Humfrey, duke of Gloucester (d. 1447). Long ago, in a previous millennium, when I was writing my doctoral thesis, I spelt his forename in what has become the more usual way, as ‘Humphrey’, and for that I was roundly reprimanded when it came to my viva. So, I always now use the spelling the duke himself used; at the point I attained my doctorate, I became an ‘f’-ing historian. The rest of the world, though, has proven slow to catch up and so now, if I type Humfrey into Google, it assumes it is an error. If I accept its suggestion of ‘Humphrey’, it comes up with many more results, but if I insist on the correct spelling, it returns a different set of results (admittedly, with my work the top hit). One implication is that if I used only one spelling, I would miss relevant results. Try both.

- Phrase your searches as others would – this is the other implication of the previous point: if I insisted on what I called the ‘correct’ spelling, I would be needlessly ignoring useful results. This does not mean accepting Google is right, it simply means that what we type is guided by how others express the subject. To give another example: the rulers of sixteenth-century England never called themselves ‘the Tudors’ and to use that designation as an adjective for a swathe of time is to imply it has a shared character that did not exist — but most people use the term, so deploy it in your searches. It does not commit you to employing it when you write up your work.

- Remember that Google has several tabs — the results that it throws back at you are listed under ‘all’, but you might want to look at ‘images’. Also useful is the section under ‘books’ (from the drop-down menu of ‘more’), which is more likely to lead you quickly to published works, though what it will suggest will either be old and out of copyright or recent, in copyright and so not available to view. At that point, you need to take your search a step further, and we will discuss that in the tips that are soon to follow.

- Refine your terms time and again — the process of searching is not one process undertaken at a single moment. What you find will lead you in new directions or spark some lateral thinking. Add those to your list of search terms and pursue them.

- Keep your page or file – it will become useful later, as we will explain in tip IX.

Next time: yes, do use Wikipedia as a springboard for your research.

Do feel free to comment, and let me know what your own tips.

1 comment